September 20, 2023

In Focus - India’s goods exports

India has had a strong stretch of months on the world stage. In its July World Economic Outlook, the IMF projected it to be the world’s fastest growing large economy over the next two years. Just weeks earlier, the country successfully launched its first unmanned mission to the moon. More recently, it hosted the G20 leaders summit in New Delhi, where trade was atop the agenda. On trade, however, India has largely struggled to achieve escape velocity from the pull of protectionism.

India’s August trade figures, released last week, showed a 6.8% year-on-year drop in goods exports in nominal US dollars. Adjusted for inflation the decline was far less severe, or only 0.8%. Year-to-date through August, however, India’s real exports are 6.0% below 2022.

First, a somewhat encouraging take. As we’ve stressed before, 2021 / 2022 were unique years that fed unrealistic expectations about trade growth, leading to a lot of the overhang that is now weighing on countries and firms up and down the supply chain. As the chart below shows, India’s real goods exports – deflated using the Wholesale Price Index – were down only slightly from 2018 to 2019 before shrinking 15.8% year-on-year in 2020. If we bypass the pandemic years to 2023, year-to-date exports are up 7.3% over the same period in 2019. At an annualized rate of 1.8%, that is solid, if unspectacular growth.

A less encouraging take might be that, for a country of more than one billion people with ambitions to become a global trading power, that is … solid, if unspectacular growth. India’s 2023 Foreign Trade Policy set an ambitious target of $2 trillion in exports by 2030, split evenly between goods and services. Assuming India’s goods exports over the next four months bring the year-end total to around $300 billion (itself a tall order), that would require a compound annual growth rate of 18.8% to reach $1 trillion.

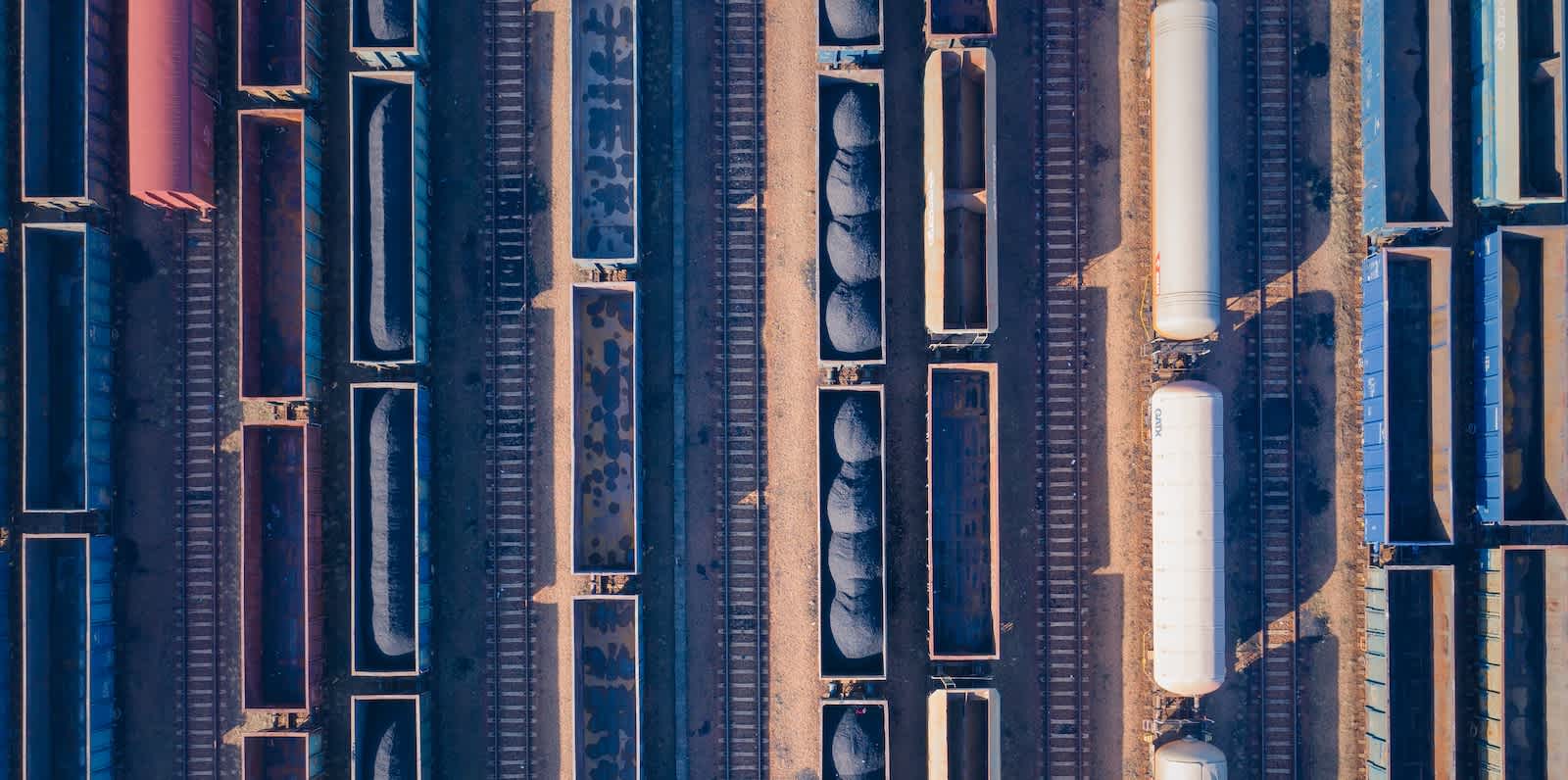

Infrastructure is often pointed to as the main constraint on the country’s export potential. Depending on how much store you put in global infrastructure and logistics rankings, that appears to be less a factor than it once was. The World’s Bank latest Logistics Performance Index, for example, ranks India 38th out of 139 countries, ahead of Portugal, Turkey, Vietnam, Chile and Indonesia and it’s just outside the top-20 on the ‘International shipping’ sub-indicator.

These exercises tend to be more art than science, notwithstanding scores to the decimal point. But if we’re being generous, they are probably broadly representative of actual conditions.

What deserves more attention is India’s trade policy, particularly when it comes to tariffs. It’s no secret that India has long levied among the highest import duties in the world and as of the WTO last Trade Policy Review in 2021, they were inching back upward. What makes India’s tariffs so detrimental to its export goals is that in many industries they are inverted rather than escalating. Escalating tariffs increase the more value is added to a good, with the lowest tariffs on raw materials and the highest on finished goods. Under an inverted tariff structure, tariffs in certain goods value chains are lower on finished goods and higher on raw materials and other inputs. Think higher tariffs on rubber than on tires, on copper than on insulated copper tubing or on stainless steel for a range of products. This can discourage domestic manufacturing when there is little to no domestic alternative supply.

The most prominent example of this self-imposed constraint being overcome is smartphones. And indeed, India has attracted major contract manufacturers for leading smartphone brands over the last few years. In the 18 months since April 2022, when it began using a dedicated Harmonized System (HS) code for smartphones (8517 13 00), exports have increased an average of 7.2% per month, with single-month peaks of over $1 billion in January and March this year.

Whether this is replicable in other sectors is far from certain. Arguably, it could prove an isolated case; the interplay between trade policy, investment incentives and global developments is especially complex in smartphone production.

First, the tariff structure for smartphones is neither escalating nor strictly inverted. The duty on smartphones is 20%. The tariff on components range from zero (chips) to 15% (lithium ion batteries) to 20% or higher (transmission mechanisms, for example). Second, the government’s Production-Linked Incentive Scheme indirectly compensates firms for the higher cost of imported inputs as a result of the tariffs. And third, India benefited from economic and geopolitical tensions that affected trade in smartphones in a way that it won’t for less sensitive products.

India’s rocket scientists surely spent years calculating drag and friction for the rocket that sent Chandrayaan-3, the lunar module, on its way to the south pole of the moon. Its policymakers might consider a similar approach to reduce drag and friction on export, starting with tariffs on inputs.

Disclaimer: The contents of this report are made available for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon for any legal, business, or financial decisions. Flexport does not guarantee, represent, or warrant any of the contents of this report because they are based on our current beliefs, expectations, and assumptions, about which there can be no assurance due to various anticipated and unanticipated events that may occur. This report has been prepared to the best of our knowledge and research; however, the information presented herein may not reflect the most current regulatory or industry developments. Neither Flexport nor its advisors or affiliates shall be liable for any losses that arise in any way due to the reliance on the contents contained in this report.